CHRONOLOGY

From his parents, Weinberg

inherited his penchant for hard work. But his

artistic ambition was just an accident, he believes,

or perhaps the result of one. "It may all come down

to the fact that I hurt my eye when I was about

four," he theorizes. The eye was saved but his

vision was permanently impaired. He was left

with distorted depth perception, able to see

only impressions out of his right eye. Throughout

his childhood, there was great concern about

his ability to see.

Still, from the day he

picked up a crayon, he showed promise. "Copying Mickey Mouse and

Donald Duck on shirt cardboards - that was my

specialty. My father had his shirts laundered,

and they all came back on shirt cardboards. That

was my favorite medium." He traces the birth

of his predilection for sculpture to his three-dimensional

projects. He was always building soapbox derby

racers, burglar alarms, submarines.

But it was

his youthful passion to create that won his

parents over. When he was 14, he made a small

clay relief and accidentally broke it while

trying to cast it in plaster. It made him cry

desperately, his mother recalls. If it's that

important to him, she decided, he ought to

have lessons. So she called Henry Kreis, a

German sculptor living in Essex, Connecticut.

Kreis was teaching at the Hartford Art School

then housed in the Wadsworth Atheneum, and

he suggested that young El enroll. So he lied

about his age and studied there at night throughout

high school. It was a rigorous schedule, but

he surmounted it to become valedictorian of

his class at Weaver High in 1946... After graduating,

Weinberg enrolled at the art school full time

and continued to study with Kreis, whom he

idolized and to whom he credits his preference

for lyrical, figurative work. He was equally

devoted to Waldemar Raemisch, another German,

with whom be studied upon transferring to the

Rhode Island School of Design after two years. "He couldn't express himself in English," Weinberg

says. "He was just a tremendously inspirational

person-- his work and his love of art."

Under Raemisch he studied

hard, but it was a labor of love. "When I was in art school, I

had my own studio and boy, I worked." ...He worked

at a car wash, painted flowers on furniture,

taught arts and crafts at a boys' club. Meanwhile,

he slaved away in his studio, an abandoned bathroom

at the Volunteers of America, the home for derelicts

in which he lived his first year. "I paid $2

a week, and I lived on crackers and jelly given

by the Colonel, who ran the place. I lived with

all the down-and-out guys, and the Colonel --

I'll never forget him -- he kept us alive." Under Raemisch he studied

hard, but it was a labor of love. "When I was in art school, I

had my own studio and boy, I worked." ...He worked

at a car wash, painted flowers on furniture,

taught arts and crafts at a boys' club. Meanwhile,

he slaved away in his studio, an abandoned bathroom

at the Volunteers of America, the home for derelicts

in which he lived his first year. "I paid $2

a week, and I lived on crackers and jelly given

by the Colonel, who ran the place. I lived with

all the down-and-out guys, and the Colonel --

I'll never forget him -- he kept us alive."

Ultimately, all this diligence

and deprivation paid off. After graduating at 23,

Weinberg became the youngest recipient to ever

have won the Prix de Rome, entitling him to two

years of study in Italy. There, he met poets, painters,

and musicians, and discovered that, for an artist,

Europe is not just an ocean away but a world apart. "You get up

in the morning and you go out

and greet your friends. In America,

they say, 'How's business? How much did you

make this month?' Whereas in Europe they ask

you what you're making or what you're doing.

They don't ask you how much you sold this year.

Art is business here, and that's not what it's

all about."

Upon returning

home, he underwent not only cultural

jet lag but future shock. He

had accepted a scholarship at

Yale School of Design, which

involved assisting the master

sculptor, José de

Rivera, an abstract purist whose work was based

on precise, mathematical concepts. The head of

the school was Josef Albers, the famed German-born

abstractionist best known for his series of paintings "Homage

to the Square." It was Albers who had summoned

Weinberg from Rome. "Come back and teach the

figure," he had written. "Even though I don't

believe in the figure, I think it should be

taught in my school."

Weinberg complied,

only to be stylistically ostracized

and denounced by the dictatorial

Albers in front of his students. "The prevailing mode

in the sculpture department was a certain kind

of pure abstraction. I did not fit in. And I

could not adapt. It wasn't my way." But try he

did, for three years. He felt it was an inevitable

confrontation. "It was like 'How to Live with

the 20th Century' -- a decompression chamber.

How to co-exist. How to learn to take from

it without letting it upset me..."

|

"Ritual Figure," Museum of Modern

Art |

While living in Rome,

he had been given his first commission by a visiting

couple from his hometown, Marcus and Bluma Bassevich.

Weinberg had it on display in his living room at

Yale, where it was spied by a visiting trustee

of the Museum of Modern Art. "Ritual Figure", a

woodcarving of a man blowing a shofar, was an unusual

piece, but not for Weinberg; it had two arms growing

out of one shoulder. "When they said they'd buy

it, I remember rushing through the streets into

my friend's house, running up to a girl I knew

and saying, "I've got to kiss someone." And she

was offended. "You mean, just anyone? It doesn't

matter who it is?"

"Ritual Figure" made the cover of Art in America. Soon

after, Weinberg got a knock on his door..."I hear

you sold something to the Museum of Modern Art.

I'm interested in you. "I just thought he was a

great sculptor," said Grace Borgenicht [of the

Borgenicht Gallery in New York City.] "I go by

my eye and I guess it's pretty good, because I've

stayed in business for 37 years."

Borgenicht remembers calling Joseph Hirshhorn,

founder of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington,

D.C., on behalf of a struggling client. "I said,

'Joe, there's this terrific sculptor. He doesn't

have any money to buy a piece of wood.'

So Joe gave me the money to give him to buy

the wood, and then he did a beautiful woodcarving

which they bought and put in the museum." |

In 1959 Weinberg landed a Guggenheim

Fellowship, a grant for a year of work. He decided

to return to Rome for the year and ended up staying

for 11. "It was a paradise for sculptors. They

love artists. Whether you're good or not, they

call you Maestro. 'Buon giorno, Maestro!' It's

a wonderful feeling..."

Returning to America, he taught

at Dartmouth and Boston University as visiting

Professor of Sculpture, then back in Rome at

Temple University, at Union College in New

York, and finally, starting in 1983, as Professor

of Sculpture at Boston University.

Among the major public commissions

Weinberg completed during this time were: Procession for

the Jewish Museum in New York, Jacob Wrestling

with the Angel for Brandeis University, Justice for

the Boston University School of Law, and the Holocaust

Memorial for Freedom Plaza in Wilmington,

Delaware.

In 1986, John Portman, an acclaimed

architect known for introducing the atrium

to contemporary hotel design, turned to Weinberg

to humanize the 18-story lobby of his Portman

Hotel San Francisco [now Pan Pacific Hotel.]

"Elbert has a unique way of

giving life to form, where the piece carries

with it an aura that's very special," Portman

said. He's a very warm person, and I think

it comes out in his sculpture." Weinberg's

exuberant Joie

de Danse not only illustrates his skill

in gearing a piece to complement a specific

environment, Portman believes. It is also an

exceptional, compelling work. "It just grabs

you.' he says. "Just to observe people looking

at it and see the response on their faces tells

the whole thing ... He's one of the best."

Weinberg's early subjects draw

heavily on mythological and Biblical themes,

but there are also more contemporary, earthbound

motifs, such as his mad

dog series. "...People might say, 'Oh my

God, what a thing to try to do in sculpture!'" notes

Weinberg. 'An idea like that.'" He is the first

to acknowledge that these fierce beasts are

unsettling, but bristles at a suggestion that

they may not be what people want in their living

rooms: "This is not art for all," he

thunders. "What does this have to do with the

average person? Most people don't understand

art," he declares, "any more than they understand

Greek. "Art is a language, like any other language.

You have to be exposed to it, you have to learn

it. The average person, without that training,

likes things that look like reality." He poses

one hand before him. "If you saw my hand in

wood or stone, the average person would say

'fantastic!' And it would be a piece of trash!"

As a figurative sculptor, Weinberg doesn't reject reality,

but often departs from it radically to offer his own

interpretation. |

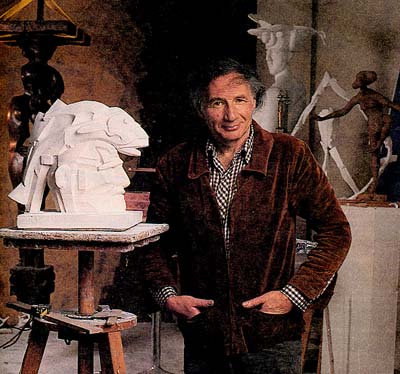

Weinberg used to work

on one piece at a time. First, he would make

a series of drawings. Then, on one special day,

when he was feeling at his best, he would sit

down and fashion a model. Once satisfied, he

would spend nine months making the piece--carving

it in wood or casting

it in bronze. Then he would start another."Now

I'm working on 20 pieces at the same time," he

says. "And I'm enjoying working more than I ever

have in my life."

After years of exercising

his imagination, he has honed his mental muscles

into tiptop shape. Even the craft part comes

easier now. "There's something about having

done it for so many years that you get familiar

with the process. It's more like talking. It's

part of you...I feel anything I conceive, I

can make," he says. "I am whistling and hopping

here in the studio now. I mean, it can be painful

when a thing doesn't come out right. But I'm

getting kicks all the time." |

Natural

History III  The

Hartford Courant, March 20, 1988 The

Hartford Courant, March 20, 1988

|

--Adapted

from article in The Hartford Courant Northeast

Magazine, March 20, 1988, by Patricia Weiss. --Adapted

from article in The Hartford Courant Northeast

Magazine, March 20, 1988, by Patricia Weiss.

Elbert Weinberg died in

December of 1991 of myelofibrosis, a rare disease

of the bone marrow that was diagnosed ten years

earlier. The Elbert Weinberg Trust has been established

to preserve his work and to ensure that the work

of this sculptor of genius continues to receive

the recognition it deserves. All works shown here,

except public commissions, are for sale. Each is

marked as limited edition, open edition, or one-of-a-kind

original.

|

|